How Far Can You Go?

On Education, Belonging and the Courage to Welcome

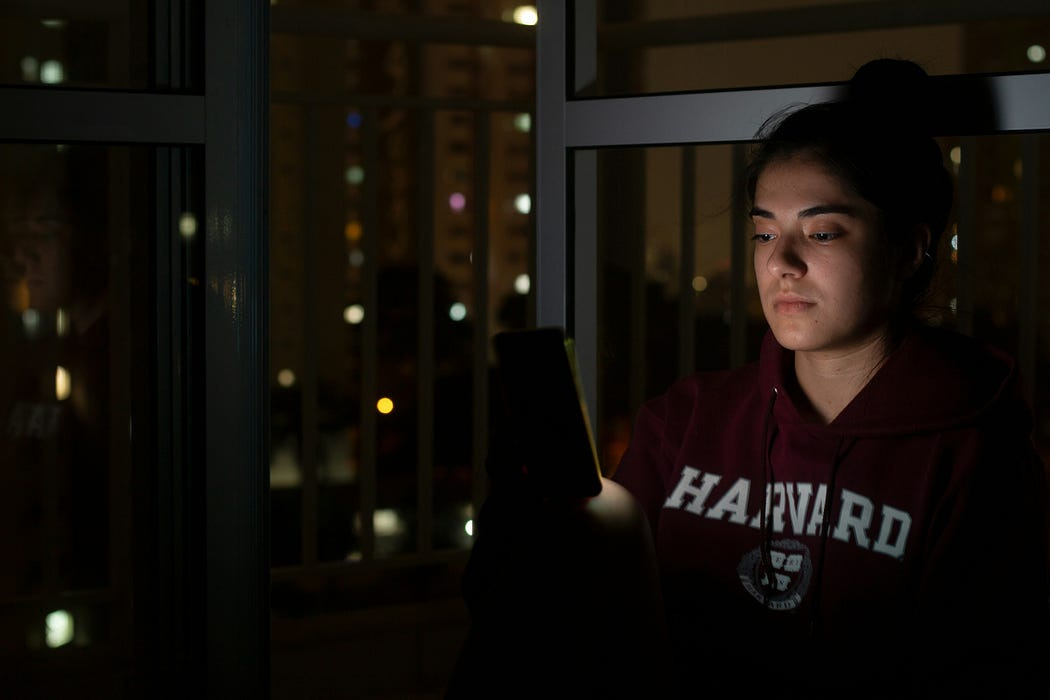

I was twenty-four years old and freshly disillusioned, when I asked myself, ‘How far can I go?’ Away from my corporate job in Bangalore, away from a broken heart and away from a grandfather who was keen that I get married. How far can I go to expand my mind, my heart, my life?

Theoretically, Harvard University felt as far as I could go. Even though for someone like me, it seemed impossible to get there. I grew up in a middle-class family in a small town in one of the poorest states of India. I applied nonetheless, and I could hardly believe the acceptance letter when it saw it, all groggy-eyed on a perfect spring morning. I knew in that moment that my life was about to change.

I was already the first girl in the family to get a Master’s degree and a corporate job. And there I was, all set to get a second Master’s, in a foreign country, at Harvard no less! My whole family, including my grandfather, rallied behind me, figuring out savings, bank loans and paperwork, to help me go to Harvard — a place unimaginable for my parents and grandparents. It really was as far as I could go then. It was quite the journey in multiple dimensions, and it changed the course of my life.

As it beautifully and radically does, for thousands of students every year, from all around the world.

The Trump administration’s pushback against Harvard in recent weeks and months is not just about federal funding and student visas. The mindless, sweeping raids against minorities everywhere isn’t just about legal documents. It is about who we believe deserves a chance to belong. It is about who gets to open the doors and for whom. It is about standing up for truth and not giving in to corrupt, divisive powers that be.

We are all migrants — of place, of class, of language, of possibility. In the heat of political whims, headlines and ideological battles, it’s easy to forget what college is supposed to represent. At its best, higher education is not a gate but a bridge, not a finish line but a threshold. It is where knowledge meets possibility. And it should be available, accessible and inclusive for all who are ready to cross that threshold, from near and afar.

Migration is not an exception to the human story. It is, and always has been, most of our story. From the earliest human wanderings out of Africa to the globalized world of today, the impulse to move — to seek knowledge, safety, possibility, freedom — is not a deviation from human nature. It is its purest expression.

And education, perhaps more than anything else, is the modern terrain on which that migration plays out. A student crossing into a new classroom, campus or country is stepping into a new life. Whether that was me at Harvard, my children in Singapore, or a Nigerian student in India.

The policies that shape who gets to take that step and who gets left behind, carry enormous weight. Trump’s executive order and proclamation against Harvard aims not just at an admissions policy, but at the very idea that equity matters.

The campaign against international students has since widened. Last month, the US government instructed its embassies to stop scheduling student visa interviews and expand social media vetting of applicants. The move came alongside renewed accusations that elite universities like Harvard are too liberal and not doing enough to combat antisemitism. The implications of this posture go far beyond political rhetoric.

According to the BBC, student applications to American universities have dropped by at least 30 percent due to rising fears about visa denials, surveillance and mid-course deportation.

Nearly one third of international students in the US come from India. In 2023–24, they were part of a cohort of over 1.1 million students who contributed $43.8 billion to the US economy and supported more than 375,000 jobs. These are not just numbers. They represent real people — aspiring scientists, healthcare workers, data analysts and future leaders — many of whom came to the US not just for a degree, but to become part of something larger.

At Harvard’s 2025 commencement, Dr Abraham Verghese stood before the graduating class and spoke not just as a physician and writer, but as someone who has lived through many kinds of migration. He recalled his journey from Ethiopia to India to the United States, and reminded us how much of American life, from rural hospitals to Nobel Prize lectures, is shaped by those who came from somewhere else. Quoting novelist E.L. Doctorow, he said,

‘It is the immigrant hordes who keep this country alive, the waves of them arriving year after year. Who believes in America more than the people who run down the gangplank and kiss the ground?’

Verghese reminded the graduates that character is revealed in decisions taken under pressure. ‘In the past few weeks, in the face of immense pressure, Harvard, under President Garber’s steady leadership, has been very visible for taking decisions worthy of your university’s heritage, decisions that reveal and will shape this university’s character.’

For millions of us today, as children and parents of migrants, this is such a moment. Do we make room or do we hold the door closed? Do we redefine excellence or do we let it calcify?

Education should be the passport, not the checkpoint. Let us make our institutions, our policies and our hearts wide enough to welcome those still on their way and see how far they can go.